Growing up (finally) in tajwid class: memories of my dad

I'm learning what he tried to teach me more than 40 years ago.

At my online tajwid class today, I whined about not being able to produce a “lam” sound reliably. As always, my ustadha, who studied tajwid in Damascus for years, had a great suggestion. And progress was made.

About the whining, I said to her: “I really am a spoiled United States baby.” It’s the truth. Other people have noticed: most memorably, my late dad. He tried to show me, again and again, how not to be a big baby.

When I was a kid, I would occasionally look at my dad’s “dog tags,” the little metal medallions worn by U.S. military combatants to identify them in the case of serious injury or death during combat. (Sadly I no longer have them.) His dog tags gave his full name, his birth date (1918), and his place of birth (northeastern Pennsylvania). He was born just before World War I ended, and served as a radioman in the United States’ Pacific campaign during World War II. It was there than he came down with lupus erythematosis, about which more later. He was 47 years old when I was born, the typical late-marrying Irish bachelor of the last century. So we were two generations apart. And that’s significant too.

My dad, even though he was a staunch Catholic, would have been pleased by the notion of husband and father as khalifa. On the rare occasions when I was prepared to listen, I got good guidance from him. He correctly saw me as someone with a tendency to sit on the couch, eat, and not do much of anything else. So he guided me into regular exercise (Alhamdulillah), focus on studies, and… piano lessons.

Oh, how I hated sitting at the piano. And I had a natural gift for music. Didn’t matter. I would rattle through my lessons, sight-reading as I needed, and wrap up in 30 minutes. As a kid, I was able to get pretty far on those fumes, doing my lessons, going to my teacher, checking off the box. And as I touched the keys, my mind would be 1,000,000 miles away. Eventually my dad gave the OK for me to stop taking piano lessons, although I never found out how he felt about that.

We didn’t have a great relationship. He was wrestling with a serious illness which required him to take prednisone, a steroid with a lot of nasty side effects, including mood volatility. More to the heart of the matter: I resented him for imposing ANY kind of discipline. What’s more, And like I’ve said here before, my nafs is of the kind that wants me watching mindless TV and eating 6,000 calories a day, every, single, day. It was like that when I was a kid, and it’s like that now, except now I am far more torn about letting it lead me where it will.

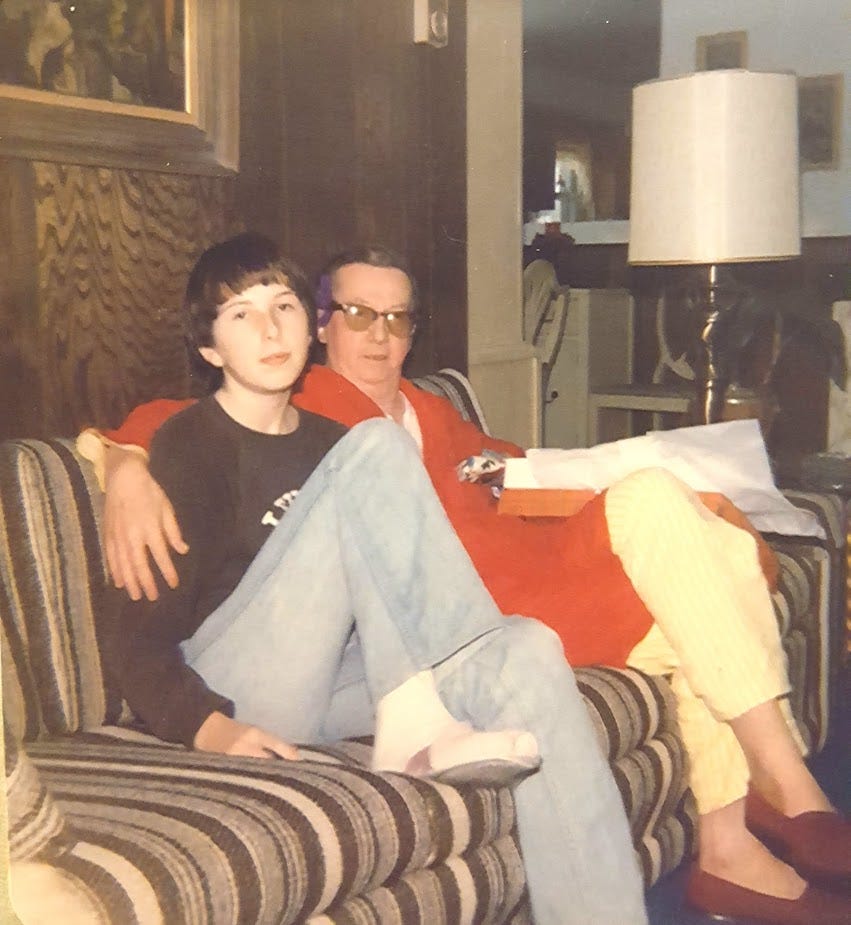

In the summer of 1981, I began to see him in a slightly different light. Something shifted. I gave him a manicure at one point, because the lupus meant he had to maintain his fingernails and toenails to avoid fungus. Now, it pains me to say this, but I didn’t want to touch him because of the physical manifestations of his illness. (I am not much one for touching or being touched. Autism? Alien from another planet? At age 15 I was unaware of all these things, I just knew I was uncomfortable touching him.) But I gave him a manicure anyway. And I bought him a paperback copy of “The Winds of War” by Herman Wouk for his 63rd birthday in September. He was delighted.

And that summer, I told him about my despair. He said he loved me. His love was flawed, as is the love of all humans. But I believed him then, and I believe him now.

In September of 1981, he died, unexpectedly. He had a heart attack (not his first) and was admitted to hospital, but his (excellent) physician expected he would recover. Instead, after a few days in hospital, he went into cardiac arrest. H died around 3 a.m., when some of the few Muslims in our time zone were probably up making tahajjud.

After his death, there was no more khalifa in my life. I ran amok, and did so for decades. And I had years of psychotherapy, which reinforced my belief that my parents, particularly my European-descended dad, were to blame for my current misery. I was more than happy to don the mantle of “innocent victim” and to follow my whims.

I will note that my dad’s generation may well have been the last generation of United States citizens to prioritize fundamental values and group well-being over individual pleasure-seeking. Mine, Generation X… well, look at the United States today, where many GenXers are in charge of things now, and you tell me what you see.

It is only since my shahada that my life has taken on any kind of meaningful discipline. But he was the first to show me how to lead an ethical, disciplined life. Without his example, I would been far less able to recognize how Islam appeals to our fitra.

Back to tajwid. My mind races around during salat, during everything. I do not have a soft heart for the most part, and like I’ve written here, I don’t really know how to love anyone or anything. But the practice of correct tajwid is a way that I can “show up” during salat. I can at least see that I am using my limbs in a way that begins to be respectful of my Rabb. This is further than I ever went with piano, even with writing, which is my primary form of rizq with respect to what the West deems as “talent.”

And by saying those “lams” incorrectly, being corrected, and attempting them over and over again no matter what my inner Big Baby says, I can begin to put myself in the position of an ‘abd.

My dad was born in 1917, served as a drill sergeant in WWII, and died in 1987 of an unexpected heart attack. I get a lot of what you're saying but I do feel like he did a good job of teaching me to be community-focused.

Something I read about parents of his generation that explains a lot about Boomers and older Xers is that Silent Gen parents went through a lot of hardships and tried to prepare their kids for a hard world, while fixing the world so it wasn't hard. Now people don't understand that the structures they built are what keeps the world from being a lot harder. (This is more a US pov than elsewhere but it resonates a lot for me.)

For me those instructions about how to live in a hard world were super helpful in navigating life with a progressive chronic illness and chronic pain. I'm glad you're getting what you need from your faith leaders now.